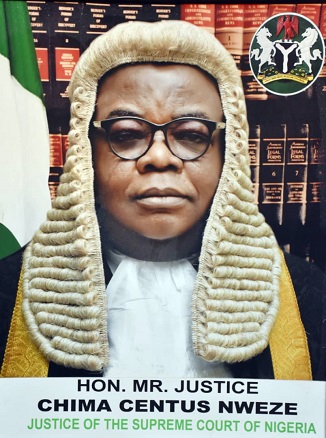

Late Hon. Mr. Justice Chima Centus Nweze, a native of Obollo, Udenu Local Government Area of Enugu State, was born on September 25, 1958. A practising Christian of the Roman Catholic Denomination, he was married to Hon Justice Ugonne Jacinta Nweze of the Enugu State Judiciary. Their union is blessed with five children and a grandchild.

ACADEMIC CAREER

He attended St John Cross Seminary, Nsukka, from 1972 -1977, emerging with a Distinction in the West African School Certificate Examination, [WASCE]. Between 1979 – 1983, he was an undergraduate student at the University of Nigeria, Enugu Campus. In 1983, he represented the Faculty of Law, and indeed, all Nigerian Law Faculties, at the Phillip Jessup International Law Moot Court Competition in Washington DC, as the Chief Oralist. Upon his graduation in 1983, [LL. B. (Hons) (Nig.)], he proceeded to the Nigeria Law School, from 1983 – 1984, where he obtained the qualifying Certificate, [BL]. He did his NYSC between 1984 – 1985 in Bauchi.

Subsequently, he returned to the University of Nigeria, Enugu Campus, between 1993 – 1995, where he studied for, and obtained, the Master of Laws Certificate, [LL. M]. Between 1997 – 2001, he studied for, and achieved, the Doctorate Degree [Ph. D.] of the same university, the University of Nigeria.

JUDICIAL CAREER

Having practised at the private Bar from 1985 – 1995, he was elevated to the High Court Bench of Enugu State in November, 1995. While on the High Court Bench, he served as Chairman, Second Robbery and Firearms Tribunal, Enugu State, 1996 -1998; Chairman, Robbery and Firearms Tribunal, Nsukka, 1998 -1999; Member, Ondo State Local Government Election Petition Tribunal, 1999; Chairman, Ogun State Governorship and Legislative Houses Election Petition Tribunal, 1999; Administrative Judge, Nsukka Judicial Division, Enugu State, 2001. He was appointed a Justice of the Court of Appeal of Nigeria, February 15, 2008; and served thereat until October, 2014, when he was, finally, elevated to Nigeria’s apex court as a Justice of the Supreme Court of Nigeria, October 29, 2014. He has been on the Bench of the Supreme Court from October, 2014 – Date.

ADHOC AND VOCATIONAL ACTIVITIES

Hon Justice Chima Centus Nweze has served in various capacities in extra-judicial vocational activities. These include: Member, DFID Access to Justice Programme, Enugu State, 2003; Member, National Working Group on the Reform of Criminal Justice Administration, 2004 [the Administration of Criminal Justice Act, ACJA, is the brainchild of this group]; Team Member, Enugu State Sector Strategic Plan, 2004; PATHS-DFID Hon Consultant, District Health System Law/Regulations, 2004; Member, OSIWARD C Expert Consultative Forum on Federal Budget Act and Facilitator, Enugu State Justice Sector Reform Team.

A former Convenor/Co-coordinator, LL. M (International Human Rights Programme), and Visiting Human Rights Scholar, Faculty of Law, University of Nigeria, Enugu Campus, 2000 -2008; Justice Nweze, who was a Distinguished Scholar, Pro Bono, Faculty of Law, Enugu State University of Science and Technology, ESUT, Enugu, was formerly, a Visiting Associate Professor of Law, Faculty of Law, Ebonyi State University and Member, International Advisory Board, Annual Survey of International & Comparative Law (Golden Gate University School of Law, San Francisco, USA).

PUBLICATIONS

A. INTERNATIONAL PUBLICATIONS

- Contemporary Issues on Public International and Comparative Law (Florida: Vandeplas Publishers, 2009) [www.vandeplaspubishing.com];

- Re-mapping the Contours: Interrogating the Ontology of International Law in a Rapidly-Changing World, [www. Digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu];

- Privacy and State Surveillance for Constitutional Values: Antinomy or Compromise? in [ISRCL 2016 -Eventegg. Com];

- “Justiciability or Judicialisation: Circumventing Armageddon through the Enforcement of Socio-Economic Rights” in Annuaire Africain de droit international Volume 15, 2007 (Leiden/Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2007) [www.ayil.org];

- “Domestication of CEDAW: Points to consider for Customary Law” in M. Shivdas and S. Coleman (eds), Without Prejudice (CEDAW and the Determination of Women’s Rights in a Legal and Cultural Context) (London: Commonwealth Secretariat, 2010) [www.thecommonwealth.org/publications];

- “The Evolving Jurisprudence of Contemporary International Criminal Tribunals: Implications for the Definition of the Core Crimes in the ICC Statute” in Contemporary Issues on Public International and Comparative (Florida: Vandeplas Publishers, 2009) [www.vandeplaspubishing.com]

(a) “Contentual Analysis and Overview of the Implementation Problematic of Codes of Judicial Conduct in Selected Commonwealth Jurisdictions”, in Commonwealth Judicial Colloquium on Combating Corruption in the Judiciary (London: Commonwealth Secretariat, 2002).

NATIONAL PUBLICATIONS BOOKS

- Beyond Bar Advocacy (Umuahia: Impact Global Publishers Ltd, 2011) (with A. J Offiah and J. T. Mogboh)

- Redefining Advocacy in Contemporary Legal Practice: A Judicial Perspective (Lagos: Nigerian Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, 2009)

- Contentious Issues and Responses in Contemporary Evidence Law in Nigeria (Volume Two) (Enugu: IDS, University of Nigeria, 2006) [www.allbookstores.com]

- Contemporary Issues and Responses in Contemporary Evidence Law in Nigeria (Volume One) (Enugu: IDS, University of Nigeria, 2003) [www.allbookstores.com]

- Current Themes in the Domestication of Human Rights Norms (Enugu: Fourth Dimension Publishers, 2003) [www.fdpbooks.com] [With Oby Nwankwo)

- Justice in the Judicial Process (Enugu: Fourth Dimension Publishers, 2002) [www.fdpbooks.com]

- Law and Procedure in Suits on the Undefended List (Enugu: Hamson Publishers, 1998)

- Legal Methods in Nigerian Law (Enugu: Hamson Publishers, 1998)

- The Catholic Clergy Under Nigerian Law (Enugu: Hamson Publishers, 1998) [With C. O. Ugwu]

- Imprints on Law and Jurisprudence (Enugu: Fourth Dimension Publishers, 1996) (With G.C. Nnamani) [www.fdpbooks.com]

- Perspective in Law and Justice (Enugu: Fourth Dimension Publishers, 1996) (With I.A. Umezulikie) [www.fdpbooks.com]

B. BOOK CHAPTERS

- “Eugenes: The Sociology of a Judicial Ideology “, in C. C Nweze (ed), Justice in the judicial Process (Chapter One);

- “Expanding the Frontiers of legal Aid Services – The Humanitarian Perspective “, in S.A Akpala (eds), Legal Aid services in Nigeria: The Humanitarian Perspective (Enugu: SWEWP, 2001) Chapter 7.

- “A survey of the shifting trends in judicial attitudes to fundamental rights in Nigeria”, in I.A. Umezuluike and C. C. Nweze (eds), Perspective In Law and Justice (supra) (see Chapter 2)

- “Continuing Professional Education for Law Library Staff”, in Oluremi Jegede (ed), Law Libraries in Nigeria: Match to the 21st Century (Lagos: Association of law libraries, 1998) (See Chapter 7).

- “Evolution of the Concept of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in Human Rights Jurisprudence: International and National Perspectives”, in Eze Onyekpere (ed) Manual on the Judicial Protection of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. (Lagos: Shelter Rights Initiative, 2000)

- “Judicial Sustainability of Constitutional Democracy in Nigeria: A Response to the Phonographic Theory of the Judicial Function”, in E.S.Nwauche and F. Asogwa (eds), Essays in Honour of Prof. C.O. Okonkwo (SAN), (Port Harcourt: Jite Books, 2000) (Chapter 11)

- “Neither Bird Nor Mammal? Is the Magistrate a Judicial officer, a Civil Servant or a Public Officer?”, in D.C. Ezeani (ed), Neither Bird Nor Mammal?(Enugu: FDP, 2004) Chapter Two

- ”The Evidential Landscape in Cyberspace: Implications of Technological Developments on the Law of Evidence in Nigeria” in A. I. Chukwuemerie (ed), Growing the Law, Nurturing Justice (Port Harcourt: Lawhouse Books, 2005)

- “Respective Federal/ State Jurisdictions on Critical Issues under the 1999 Constitution”, in N. Tobi (ed.), A Living Judicial Legend (Lagos: Florence and Lombard, 2006) Chapter 4

- “Jurisdiction of the State High Court”, in Jurisprudence of Jurisdiction (Abuja: Oliz Publishers, 2005) Chapter 5

- “Definitions of Crimes in the Rome Statute: implications for the protection of Human Rights’ Norms”, in A. Onibokun and A. Popoola (eds.), Current Perspectives in Law, Justice and Development: Essays in Honour of Justice of Justice Belgore (2007) chapter 24

JOURNAL ARTICLES

- “Human rights and sustainable development in the Africa Charter: A juridical prolegomenon to an integrative approach to Charter Rights,” (1997) Abia State University Law Journal. Volume 1, February 1997, 1 – 18

- “Antinomy of Rights: Human Rights Perspectives on the Recovery of Premises Procedure”, in LASER Contact Vol. 4. No. 1 January – June, 2000.

- “The Judiciary: The Guardian of Democracy under the Constitution”, UNIZIK Law Journal Vol. 1 No. 3.

- “Judicial Integrity: Desideratum for good governance”, Jos Bar Journal 2003.

- Book Review: Introduction to Civil Procedure, Nigerian Bar Journal Vol. 1 No. 4, 2003.

- Book Review: Selected Essays of Hon. A. G. Karibi Whyte on Jurisprudence, NBA Journal, No. 4 Vol. 2

- “Issues and Options in the Domestication of the ICC Statute in Nigeria”, Nigerian Bar Journal, Vol. 2 No. 1, 2004.

- “Reflections on Selected Judicial Decisions on Women’s Rights”, UNIZIK Law Journal. Vol. 4 No. 1, 2004.

- “Legal Regulation of Budgeting in Nigeria”, in Journal of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Vol. 1 No. 4, April –June 2002, 1-19

- “The Right to Physical Comfort at the Hearing…”, Nigeria Bar Journal, Vol. 1 No. 2, April, 2003

- “The Impacts of Legal Aid Services in the provision of Access to Justice to the Poor in Nigeria”, in SWEWP 10th Anniversary (Enugu: SWEWP, 2003) P. 23.

- “The Role of Nigerian Courts in Human Rights Enforcement”, in Court Room vol. 14 No. 3

- “The Christian Option in a Corrupt Society”, in Bigard Theological Studies vol. 26 No. 1 (January to June 2006) p. 71.

- “Medical Negligence: Comparative Contemporary Legal Perspectives,” in Consumer Journal Vol. 1 No. 1 (2005

- “Confronting the Leviathan: Overview of the Constitutional Framework for transparency in Public office”, in Mind- Opener (2005) Vol. 2.

INTERNATIONAL EVENTS ATTENDED

- Silver Jubilee Fulbright Symposium, Golden Gate University, San Francisco, California, USA, 2015;

- World Jurists Association, Warsaw, Poland, 2015;

- Session of the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights, Banjul, The Gambia, 1999.

- Session of the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights, Pretoria, South Africa.

- World Conference on Penal Reform, Burkina Faso, 2002.

- International Retreat on the Future of Nations State, Klingenthal, nr. Strasbourg, France, 1999.

- International Conference on the International Criminal Court, Accra, Ghana, 2003.

- International Seminar on Litigating Socio-economic Rights, Swedru, Central Region, Ghana, 2004.

- Commonwealth Judicial Colloquium on Combating Corruption in the Judiciary, Cyprus, 2002.

- Commonwealth Colloquium on the Domestication of CEDAW, Yaounde, Cameroon, 2006

- African Group of the International Association of Judges, Yaounde, Cameroon, 2006

- Regional Human Rights Conference, Dakar, Senegal, 2007

- International Conference on Africa and the Future of international Criminal Justice, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, July, 2010.

- Society for the Reform of International Criminal Law, Ottawa, On. Canada, July, 2011

- Advanced ICT Conference, Dubai, UAE, July, 2012

- World Jurists Association Conference, Warsaw, Poland, 2015;

- Keynote Speaker, Golden Jubilee Annual Fulbright Symposium, Golden Gate University, San Francisco, California, USA, 2015;

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON THE REFORM OF CRIMINAL LAW, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, 2016;

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COUNTER TERRORISM, Nothingham, UK, 2017

HONOURS AND AWARDS

Justice Chima Centus Nweze is a recipient of numerous awards. These include:

Nancy Pelosy Congressional Award, 2015;

Distinguished Scholarship Awardee, Golden Gate University, San Fransisco, California, USA;

Justice of the Year Award, 1997;

Rotary International District 1940 Award, Rotract Club, UNEC: Award for Professional Service, 1998;

Dignity of Man Award, UNN Alumni Association, 2001;

Award for Excellence, Law Students’ Association, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka;

Pan-African Distinguished Leadership Hall of Fame Certificate of the African Students’ Union Parliament, 2016;

Fellow, Chartered Institute of Arbitrators, Chartered Institute of Arbitrators, Nigeria, 2015.

SELECTED REPORTED LEADING JUDGEMENTS OF C. C. NWEZE, JCA (as he then was)

-

- Arowosaye v. Ogedengbe & Anor (2009) 30 WRN 28; (2008) LPELR -3701 (CA)

- Folorunsho Kazeem v. The State (2009) 29 WRN 43S

- Falodun v Ogunse (2010) All FWLR (pt 504) 1404

- Asinlola v Fatodu (2009) 10 WRN 155

- Unity Bank Plc v Kay Plastics Nig Ltd (2009) LPELR -8839 (CA)

- Fatoyimbo v Dada (2009) 47 WRN 153; (2009) 16 NWLR (pt1168) 605

- KSWC v AIC (Nig) Ltd (2009) 47 WRN 90; (2009) All FWLR (pt485) 1738; (2008) LPELR -4414 (CA)

- Pharmatek Industrial Projects Ltd v Trade Bank (Nig) Ltd (2009) 41 WRN 65; (2009) All FWLR (pt495) 1678; (2009) 13 NWLR (pt1159) 577

- Salami v Commissioner of Police (2009) All FWLR (pt495) 1765; (2009) All FWLR (pt450) 722

- Salami v Yahayah (2009) 17 NWLR (pt 1171) 581

- Gambari v Mahmud (2010) 3 NWLR (pt 1181) 278

- Biodun Olujimi v Ekiti House of Assembly (2009) 33 WRN 44;

- Oso Onigbepa v Ayodele (2009) 33 WRN 77

- Muraino Ayantola v Action Congress (2009) 18 WRN 141

- Ibrahim Oniwara v Fulani Balogun (2009) 18 WRN 40; (2010) All FWLR (pt508) 261; (2009) LPELR -4279 (CA)

- Oladipo v Nigerian Customs Service Board (2009) 12 NWLR (Pt1156) 563; (2009) LPELR -8278 (CA)

University of Ilorin v Oluwadare (2009) All FWLR (pt 452) 1175

- Gbedu and Ors v Itie and Ors (2010) NWLR (pt 1202) 202

- Oladotun v State (2010) 15 NWLR (pt 1217) 490.

- Olateju v Sanni (2011) All FWLR (pt 590) 1257; (2011) 31 WRN 83; (2010) LPELR -4752 (CA).

- Omowaiye v AG, Ekiti State (2011) All FWLR (pt 588) 876

- Bompete Woru v State (2011) All FWLR (pt 602) 1644

- Kwara State Polythechnic v Afolabi (2010) All FWLR (pt 547) 629

- Ayorinde v Ayorinde (2011) 17 WRN 74; (2010) LPELR -3833 (CA)

- Governor, Ekiti State v Oyewo (2011) 17 WRN 48; (2010) LPELR -4216 (CA)

- Ayeni Idowu v Obasa (2011) 23 WRN 103

- Ekiti State Government v Ashaolu (2011) 15 WRN 112.

- Mansur v The Governor, Taraba State (2012) LPELR -15184 (CA)

- Manya v State (2012) LPELR -15185 (CA)

- Oyeyemi and Ors v Owoeye (2012) LPELR -19695 (CA)

- Ojuri Anjola v The State (2012) LPELR -19699 (CA)

- Habu v Isa (2012) LPELR -15189 (CA)

- Usman v Mungo (2012) LPELR -15186 (CA)

- Udotim v Idiong (2013) LPELR -22132 (CA)

- Mothercat Nig Ltd v Regtd Trustees, FGAN (2013) LPELR -22118 (CA)

- Adebowale v State (2013) 16 NWLR (pt 1379) 104

- Lucky Jacob Akpan v The State (2014) LPELR -22740 (CA)

- Akpan v Nsidibe Rufus Sam (2014) LPELR -22516 (CA)

- Nsima v Nig Bottling Co Plc (2014) LPELR -22542 (CA)

- Owners MT “Venturer” v NNPC (2014) 2 NWLR (pt 1390) 74

- Eseu v The People of Lagos State (2014) 2 NWLR (pt 1390) 109

- National Pension Commission v FGP Ltd (2014) 2 NWLR (pt 1391) 346

- Ojora v ASP (Nig) Plc (2014) 1 NWLR (pt 1387) 150

- Akpan v State (2014) LPELR -22740 (CA)

- Akobi v Osadebe (2014) LPELR -22655 (CA)

- Enterprise Bank Ltd and Anor v Aregbola and Anor (2012) LPELR -19692 (CA)

- Kings Planet Int’ v CPWA Ltd (2013) 2 NWLR (pt 1392) 605.

SELECTED REPORTED NOTABLE PRONOUNCEMENTS OF:

NWEZE, JCA (as he then was) FOREIGN DECISIONS AND THE DECISIONS OF THE APEX COURT

Per Nweze JCA (as he then was) in Ojora v ASP (Nig) Plc (2014) 1 NWLR (pt 1387) 150, 193, paragraphs A – G:

“…we find it curious that the learned senior counsel for the appellant could invite us to jettison the position of the Nigerian Supreme Court in favour of the position taken by the Court of Appeal in England on joinder. As shown above, the appellant’s counsel had contended that the English Court of Appeal in Guthrie v Circuit (supra) held that Amon v Raphael Tuck and Sons Ltd (supra) was ‘too narrow to represent the position of the law’, see paragraph 2.14 [page 8 of the reply brief]. Wonders shall never end.

As indicated earlier, our apex court, approvingly, adopted the said Amon v Raphael Tuck and Sons Ltd (supra) in Uku and Ors v Okumagba and Ors (supra) and Peanock Investment Co Ltd (supra). It, therefore, beats our imagination how learned senior counsel expected this court to denigrate the authority of the final court in Nigeria in favour of the view of a subordinate foreign court.

We do not intend to say more on this. Suffice it to note that, like the Centurion at Capernaum in the Christian Bible, this court is under authority – under and subordinate; indeed, submissive to – the authority of the Supreme Court. Thus, irrespective of whatever any foreign court may postulate, we are bound by the authorities of Uku and Ors v Okumagba and Ors (supra) and Peanock Investment Co Ltd (supra). It is only if, and only if, the apex court vacates its reasoning in the said cases that we can no longer follow them. That is the discipline warranted by the impregnable rule of stare decisis, Odi v Osafile [1985] 1 NSCC 14; Abdulkarim v Incar Nig Ltd [1992] 7 NWLR (pt pt 251); First Bank of Nig Plc v Alhaji Salman Maiwada (2012) LPELR-SC.204/2002; Bucknor-Macleen v Inlaks Ltd [1980] 8-11 SC 1; Bamgboye v Olusogo [1996] 4 SCNJ 154; Okulate v Awosanya [2002] 2 NWLR (pt 246) 530; Rossek v ACB Ltd [1993] 8 NWLR (pt 312) 382; Ewete v Gyang [2003] 6 NWLR (pt 816) 345; Adegoke Motors Ltd v Adesanya [1989] 3NWLR (pt 109) 250.”

JURISTIC PERSONALITY

Per Nweze JCA (as he then was) in Mothercat Nig Ltd v Regtd Trustees, FGAN (2013) LPELR-22118 (CA) 23-24 EC: “We take the liberty to state that our law attributes juristic personality, that is, the capacity to maintain and defend actions in court to natural persons and artificial persons or institutions, Geneva v AfriBank Nig Plc (2013) LPELR; Attorney General of Federation v All Nigeria Peoples Party and Ors [2003] 12 SCM 1, 12; [2003] 18 NWLR (Pt. 851) 182; [2003] 12 SC (Pt. 11) 146. They are, therefore, known to law as legal persons, Alhaji Afia Trading and Transport Company Ltd v Veritas Insurance Company Ltd [1986] 4 NWLR (Pt. 38) 802. In consequence, only natural persons or a body of persons whom statutes have, either expressly or by implication, clothed with the garment of legal personality can prosecute or defend law suits by that name, Knight and Searle v Dove (1964) 2 All ER 307; Admin Estate of Gen. Sanni Abacha v Eke-Spiff and Ors (2009) 3 SCM 1; [2009] NWLR (Pt.1139) 92.”

PROOF OF INCORPORATION

Per Nweze JCA (as he then was) in Mothercat Nig Ltd v Regtd Trustess, FGAN (2013 LPELR-22118 (CA) 24-26, C-C: “From a conspectus of a host of Supreme Court decisions, we are emboldened in our view that the only permissible mode of proving the legal personality of Incorporated Trustees under Part C of CAMA, or Registered Trustees under the old Land (Perpetual Succession) Act, when the adversary has not conceded that status to the plaintiffs, is by the production in evidence of the certificate of incorporation issued by the Corporate Affairs Commission [CAC], Geneva v AfriBank Nig Plc (supra); ACB Nig Plc v Emotrade Ltd (supra). Thus, where a group of persons claims to have been registered as Incorporated Trustees under Part C of CAMA, they have to produce their certificate of incorporation, as nothing else would suffice, Emotrade. In effect, for Incorporated Trustees to establish their juristic personality, except if it is admitted by the opposing party, they must tender their certificate of incorporation under Part C of CAMA. It is, thus, not enough to describe themselves as Incorporated Trustees, Bank of Baroda v Iyalabani Company Limited, [2002] 12 SCM 7. Indeed, there is even a binding authority which favours the view that the status of Incorporated or Registered Trustees can only be established as a matter of law by the production in evidence of the certificate of incorporation under Part C of CAMA, whatever may be the admission of the defendants, Registered Trustees of Apostolic Church v AG Mid-West (supra); Geneva v AfriBank (supra); J.K. Randle v Kwara Breweries Ltd [1986] 6 SC 1.

ON JURISDICTION

Per Nweze JCA (as he then was) in University of Ilorin v Oluwadare (2009) All FWLR (pt 452) 1175 at 1204: “ …jurisdiction is to a court what a gate or door is to a house. That is why the question of a court’s jurisdiction is called a threshold issue: it is at the threshold [that is, at the gate] of the temple of justice [the court]. To be able to gain access to the temple [that is, the court], a prospective litigant must satisfy the gate keeper that he has a genuine cause to be allowed ingress. Where he fails to convince the gate keeper, he will be denied access to the inns of the temple. The gate keeper, as vigilant as he is always, will readily intercept and query all persons who intrude in his domain.”

ON CONSTITUTIONAL TIME FRAME

Per Nweze JCA (as he then was) in Ibrahim v Fulani (2009) LPELR 3279 (CA): “…it is the Constitution, the most fundamental law in Nigeria, which originated the idea of time frames in respect of the tenure of the elective political offices to which election matters are tied. Thus, for the effectuation of this irreversible constitutional time frame, the factor of expeditious disposal of election petitions makes it imperative that time must be reckoned with. Indeed, anything short of that may even amount to sabotage against the raison d’etre for inaugurating periodic elections into elective offices in a constitutional democracy such as ours, Maduako v Onyejiocha (2009) 5 NWLR (pt 1134) 259, 275; Khalil v Yar’ Adua (2003) 16 NWLR (pt847) 446; Amgbare v Sylva (2007) 18 NWLR (pt.1065) 1.”

GROUND OF LAW AND GROUND OF MIXED LAW AND FACT

Per Nweze JCA (as he then was) in Kwara State Water Corp v AIC Nig Ltd (2008) LPELR-4414 (CA) 25-26, paragraphs C-F: “The courts have very often confessed the difficulty in distinguishing a ground of law from a ground of mixed law and fact, Ogbechie v Onochie (1986) 1 NWLR (pt. 70) 370 (where Eso JSC approvingly adopted the scintillating expose on the subject by C. T. Emery and Professor B. Smythe in their article titled, ‘Error of Law in Administrative Law’, in Law Quarterly Review Vol. 100 (October 1984); UBA Ltd v Stahlbau Gmbh & Co (1989) 3 NWLR (110) 374, 391-392; Obatoyinbo v Oshatoba (1996) 5 NWLR (pt. 450) 531, 548; MDPDT v Okonkwo (2001) 3 KLR (pt.117) 739 etc. This handicap, notwithstanding, they have ingeniously fashioned out formulae for navigating through the nuances of the characterisation of the grounds. The first formula aims at facilitating the ascertainment of what constitutes a ground of appeal. It comes to this: a court has a duty to do a thorough examination of the grounds of appeal filed. The main purpose of the examination will be to find out whether – if from the grounds of appeal, it is evident that the lower court misunderstood the law or whether the said court misapplied the law to the facts which are already proved or admitted. In any of these two instances, the ground will qualify as a ground of law. On the other hand, if the ground complains of the manner in which the lower court evaluated the facts before applying the law, the ground is of mixed law and fact. The determination of grounds of fact is much easier. Put in very simple terms, this formula simply means that it is the essence of the ground; the main grouse: that is, the reality of the complaint embedded in that name that determines what any particular ground involves, Abidoye v Alawode (2001) 3 KLR (pt. 118) 917, 919; NEPA v Eze (2001) 3 NWLR (pt. 709) 606; Ezeobi v Abang (2000) 9 NWLR (pt. 672) 230; Ojukwu v Kaine (2000) 15 NWLR (pt. 691) 516. In effect, it is neither its cognomen nor its designation as “Error of Law” that determines the essence of a ground of appeal, Abidoye v Alawode (supra) 927; UBA Ltd v Stahlbau Gmbh & Co (1989) 3 NWLR (110) 374, 377; Ojemen v Momodu (1983) 3 SC 173.

On Academic certificates

Per Nweze JCA (as he then was) in Salami v Commissioner of Police (2009) All FWLR (pt 495) 1765; (2009) All FWLR (pt 450) 728: “An academic certificate is an invaluable treasure. The route to its attainment must be characterised by transparency; perseverance; discipline and hard work. These factors make its achievement a mark of distinction; a thing of pride! Nothing, therefore, must be done to taint its purity, its appeal! Let us not do anything to scandalise our academic certificates in the eyes of the discerning international community.”

ON WHEN A CANDIDATE QUALIFIES AS A UNIVERSITY STUDENT

Per Nweze JCA (as he then was) in Folorunsho Kazeem v. The State (2009) 29 WRN 43: “A candidate becomes a student of a University when, upon fulfillment of all entry requirements, he is not only offered admission, but he, actually, takes the prescribed oath and enters his name in the Register of the University. Upon entering his name in this Register, also known as the Matricula (from the Latin etymon matricula), he becomes a matriculant, that is, an enrolled or registered student of the said University. That explains why the inaugural ceremony in which the student actualizes his membership of the University community is referred to as matriculation. By his registration, he acquires the status of a student. The Constitutive Act of each University delimits the tenure of such a registered student depending on his discipline or choice of study. Such a registered student remains a bona fide member of the university and will only shed that toga upon graduation in character and learning!” On the effect of the suspension of a student from a University Per Nweze JCA (as he then was) in Folorunsho Kazeem v The State (2009) 29 WRN 43: “The word, suspend, traces its roots to the old French word suspendre, which yielded the Latin variant, suspendere. It is the act of removing some one from a place temporarily as a punishment. In this particular context, suspension is the act of sending a student out of a University for a definite period as a punishment. It is, thus, the comeuppance for his deviance! This punishment merely disrupts, but does not truncate, his tenure in the University. It merely puts it in abeyance. When he purges himself of his misconduct, he resumes his tenure.”

On the award of University Degrees

Per Nweze JCA (as he then was) in University of ILorin v Idowu Oluwadare (2009) All FWLR (pt 452) 1172: “…the entire processes culminating in the award of a University degree possess, and should rightly be conceded, an aura of inviolability and sacrosanctity. Thus any action that is capable of denuding the integrity of those processes must be viewed with askance! That is why no court should be allowed to nibble at the authority of the Senate of a University, the Senate, being the ultimate guardian of the sanctity and integrity of the degrees issuing forth from the University. Above all, a University degree is not a commodity that can be purchased in any super-market. Unlike the purchase of other commodities, the achievement of a degree is characterised by the twin attributes of distinction in character and learning! The net effect is that notwithstanding the acerbity of its tirades, no court can harangue a University into awarding its certificate to a candidate who has not distinguished himself/herself in character and learning…”

On Universities as Ivory Towers

Per Nweze JCA (as he then was) in Professor J. A. Adeyanju v University of ILorin and Anor (2011) All FWLR (pt 569) 1080, 1207: “Universities, popularly referred to as ‘Ivory Towers’, are famous as citadels of learning; as centres of robust; open and engaging academic and scholastic disputations: unbridled disputations that shape and mould policies; that interrogate otiose and moribund assumptions; that generate hypotheses which, almost always engender paradigm shifts in attitudes; tendencies and societal goals.”

On powers of a University

Per Nweze JCA (as he then was) in Professor J. A. Adeyanju v University of Ilorin and Anor (2011) All FWLR (pt 569) 1080, 1208: “…a university is not a personal fiefdom where serfs, like fawners, grovel at the feet of the megalomanic lord of the manor! No! The first respondent is a creation of statute [in this case, the University of ILorin Act]. In consequence, the universe of powers exercisable by all persons and authorities in the said University must orbit within the compass of the legislative framework of that constitutive Act and such regulations as may be made there-under. Thus, any purported exercise of power, for example, the removal of an employee of the University, in utter disregard, nay more, in contravention, of the Act must be greeted with firm disapprobation as an act which is ultra vires.”

ON UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATES

Per Nweze JCA (as then was) in University of ILorin v Idowu Oluwadare (2009) All FWLR (pt 452) 1172: “Every undergraduate must endeavour to reconcile himself/herself with the ethos of the University environment. Put simply, he/she must strive to acquire the requisite temperament for the sustenance of his tenure in the University. It cannot be otherwise! After all, the University is a confluence where all noble virtues are on parade: scholarship; creativity; industry; decorum; decency; honesty; humility; urbanity and the free and the unbridled intellectual masturbation of grand ideas! Above all, the University is the academic nursery for the formation of the Nation’s future leaders: Statesmen; Jurists; Parliamentarians; Moguls of business and the Captains of Industry. Anybody who cannot abide by the tenets of these ideals must try the motor park where mayhem, eventuating from violence and brigandage, characterises the drudgery of daily existence!”

PROOF OF MURDER

Per Nweze, JCA (as he then was) in Onjuri Anjola v The State (2012) LPELR-19699 (CA) 21-22, paragraphs B-D: “…in a charge of murder, the prosecution is obliged to prove: (1) that the deceased died; (2) that his/her death was caused by the accused; (3) that she/he intended to either kill the victim or cause her/him grievous bodily harm, see, for example, Woolmington v. DPP [1935] AC 462; Hyam v. DPP [1974] 2 All ER 41; R v. Hopwood (1913) 8 Cr. App. R. 143, [England]. The Nigerian cases on these ingredients include: Madu v. State [2012] 15 NWLR (pt 1324) 405, 443, citing Durwode v. State [2000] 15 NWLR (pt 691) 467; Idemudia v. State [2001] FWLR (pt 55) 549, 564; [1999] 7 NWLR (pt. 610) 202; Akpan v. State [2001] FWLR (pt 56) 735; [2000] 12 NWLR (pt 682) 607. Elsewhere in the Commonwealth, the courts have, similarly, upheld these ingredients, R. v. Nichols (1958) QWR 46; R v. Hughes (1958) 84 CLR 170; Timbu Kolian v The Queen (1958) 42 A. L. J. R.; R v. Tralka [1965] Qd. R. 225, [Queensland, Australia]. In the recent decision of Madu v. State (supra) at page 443, the Nigerian Supreme Court provided further insights into the nature of the duty on the prosecution.

Speaking for the apex court, Ariwoola JSC opined that: …in a murder charge, prosecution owes it a duty to discharge by proving the death of the victim, responsibility of the accused by act or omission, intentional act or omission of the accused with knowledge that it could cause grievous bodily harm or death. The prosecution must prove that the act or omission caused death but not it could have caused death. The erudite and distinguished jurist cited, with approval, Ubani and Ors. v State [2004] FWLR (pt 191) 1533, 1545; [2003] 18 NWLR (Pt 851) 224; Godwin Igabele v The State [2005] 3 SCM 143, 151; [2006] 6 NWLR (pt 975) 100; Alewo Abogede v State [1996] 5 NWLR (pt 448) 270.”

USE OF DANGEROUS WEAPON

Per Nweze JCA (as he then was) in Ojurin Anjola v State (2012) LPELR -19699 (CA) 33-34, E-B: “We agree with the lower court’s inference that the deceased person’s death was a probable, and not just a likely, consequence of the accused person’s act of using ‘Makeje’ (do not touch blood) on the deceased. The learned author, P. Ocheme, The Nigerian Criminal Law, Ibidem page 203, rightly in our view, observed, relying on Adamu Garba v. The State [1997] 3 SCNJ 68, that ‘[i]f a dangerous weapon such as an iron bar or a dagger or a gun, was used, the courts will infer that death is a probable and not just a likely consequence of the accused person’s act;’ also, C. O. Okonkwo, Okonkwo and Naish: Criminal Law in Nigeria (Second Edition), ibidem page 221. In Goros Bwashi v. State [1972] 6 SC (Reprint) 55; (1972) LPELR-SC.104/1972, the weapon used was a knife.”

POSSESSION AND CONFESSION

Per Nweze JCA (as he then was) in Manya v State (2012) LPELR-15185 (CA) 34-35, G-C:

“One irrefutable proposition emerges from the statutory definitions of the substantive offence of unlawful possession and the word ‘confession’ in the adjectival Evidence Act. It comes to this: while possession is a constitutive aspect of the offence of unlawful possession, a confession, as an admission or acknowledgement of the prohibited conduct, is always subsequent to the consummation of the constitutive ingredients or elements of an offence. Its effect is to relieve the prosecution of the legal burden of proof, Adeniji v State (2001) 13 NWLR (pt 730) 375; Hassan v State (2001) 15 NWLR (pt 735) 184; Okeke v State (2003) 15 NWLR (pt 842) 25; Nwachukwu v State (2002) 12 NWLR (pt 782) 543; Torri v NPSN (2011) 13 NWLR (Pt 1264) 365, 380-381. In effect, a confession does not qualify as an ‘element of an offence’ as, tendentiously, canvassed by the learned DPP.”

THE CONCEPT OF BURDEN OF PROOF

Per Nweze JCA (as he then was) in Olateju v Sanni (2010) LPELR -4752 (CA) 34-35, F-E: “The concept of burden of proof on the pleadings has an ancient ancestry, Pickup v. Thames Ins. Co. 3 Q.B.D.594. 600; and Wakelin v. L & S. W. R v. 12 App Cas. 41, 45. Its contemporary affirmation can be found in such popular cases like Joseph Constantine Steamship Line Ltd. v Imperial Smelting Corporation [1942] AC 154.174; Seldon v. Davidson (1968) 1 WLR 1083. Leading authorities on the English Law of Evidence have endorsed this usage, see, for example, Phipson on Evidence, (11th Edition), paragraph 92; page 40: ‘Burden of proof on the pleadings.’

In Imana v Robinson (supra), Aniagolu JSC (as he then was), delivering the unanimous judgement of the Supreme Court, approvingly adopted the exposition in Phipson on Evidence (supra) as the Nigerian law on the subject:

The burden of proof, in this sense, rests upon the party, whether plaintiff or defendant, who substantially asserts the affirmative of the issue. It is an ancient rule founded on consideration of good sense, and it should not be departed from without strong reasons’. It is fixed at the beginning of the trial by the state of the pleadings, and it is settled as a question of law, remaining unchanged throughout the trial exactly where the pleadings place it, and never shifting in any circumstances whatever. If, when all the evidence, by whosoever introduced, is in, the party who has this burden has not discharged it, the decision must be against him.”

ENTRY OF AN APPEAL

Per Nweze JCA (as he then was) in Oyeyemi and Ors v Owoeye (2012) LPELR -19695 (CA) 23-24, E-G: “Like Order 3 Rule 18 (1) of the Court of Appeal Rules, 1981; Order 11 Rule (1) of the Court of Appeal Rules, 2007 is similarly worded like Order 11 Rule (1) of the 2011 Rules. Two unrelated circumstances are, clearly, distinguishable under these Rules. The first is where an appeal has been brought sequel to the proper filing of a Notice of Appeal at the court below, Ogunremi v. Dada (1962)1 All NLR 663; Adewoyin & Ors. v. Adeyeye (1962) 2 All NLR 108.

The second situation relates to where an appeal has been entered at the Court of Appeal, that is, when the Appeal Court has received the Record of Appeal and the appeal is called for hearing, Ezomo v AG, Bendel State (supra) Ogunremi v. Dada (supra); Adewoyin & ors. v. Adeyeye (supra). Put simply, these Rules recognise that there are two distinct periods: the period between the time when the appeal was deemed brought, that is, when the notice of appeal was filed, and before the record of appeal was forwarded to the Court of Appeal.

During this period, that is, when the appeal has not been entered at the Court of Appeal, the appellate Court has limited control over the proceedings as between the parties. In such a circumstance, every application should, usually, be first made to the Court below where the notice of the Appeal was given, Ogunremi v. Dada (supra).

The other period relates to the time after the record of appeal is received at the Court of Appeal. At this period, when the record has been received at the Court of Appeal, technically referred to as when the appeal has been entered at the Court of Appeal, the High Court, from which the appeal emanated, would cease to have jurisdiction, Ogunremi & Anor v Dada (supra); Ezomo v AG, Bendel State (supra); Adeleke v OYSHA [2006] 10 NWLR (pt 987) 50; Ezeokafor v Ezeilo [1999] 6 SCNJ 209; Shodeinde v Registered Trustees, Ahmadiyya Movement [2001] FWLR (pt 58) 1065.

The clear intendment of the above Rules is to foreclose the awkward possibility of parties agitating their matters at the lower and appellate courts, concurrently, Akinyemi v Soyanwo [2006] LPELR -SC 51/2001; [2006] 13 NWLR (pt 998) 496.”

MEANING AND NATURE OF DISCRETION

Per Nweze JCA (as he then was) in Udotim and Ors v Idiong and Ors (2013) LPELR -22132 (CA) 13-14, F-D: “Discretion, according to settled authorities, is not an indulgence of a judicial whim. It is the exercise of judicial judgment based on facts and guided by the law or equitable decisions, UBA Ltd v. Stalibau GMBH and Co. K. G. (1989) LPELR-3400(SC). It is the court’s epistemological tool for winnowing solid truth from windy falsehood; for dichotomizing between shadow and substance and distilling equity from colourable glosses and pretences. By its very character, judicial discretion does not brook any capricious exercise of power according to private fancies and affections. We find support for this opinion in Rook’s case (1598) 5 Co. Rep. 996, cited in Ayantuyi v. Governor of Ondo (2005) 14 WRN 67, 91.”

SELECTED REPORTED JUDGEMENTS OF NWEZE, JSC, 2015 -2017

Olubumi Oladipo Oni v Cadbury Plc [2016] 9 NWLR (pt 1516);

Segun Akinolu v State [2016] 2 NWLR (pt 1497);

Wema Securities and Finance Olc v NAIC [2015] 16 NWLR (pt 1484);

Godwin Pius v State [2016] 9 NWLR (pt 1517);

Segun Adebiyi v State [2016] 8 NWLR (pt 1515);

APGA v Al- Makura [2016] 5 NWLR (pt 1505);

FRN v Borishade [2015] 5 NWLR (pt 1451);

Apeh and Ors v PDP and Ors [2016] 7 NWLR (pt 1510);

Omisore v Aregbesola [2015] 15 NWLR (pt 1482);

Amadi v Amadi [2017] 7 NWLR (pt 1563);

Mohammed Ibrahim v State [2015] 11 NWLR (pt 1469);

/Tajudeen Iliyasu v State [2015] 11 NWLR (pt 1469);

K. K. K. Holdings Nigeria Ltd v FBN Plc [2017];

Okey Ikechukwu v FRN [2015] 7 NWLR (pt 1457);

Jerry Ikuepenikan v State [2015] 9 NWLR (pt1465);

Bulet Inter Nig Ltd v Olaniyi [2016] 10 NWLR (pt 1521);

Dakan and Ors v Asalu and Ors [2015] 13 NWLR (pt 1475);

Udom Emmanuel v Umana and Ors [2016] 12 NWLR (pt 1526);

FRN v Dairo [2015] 6 NWLR (pt 1454);

Osuagwu v State [2016] 16 NWLR (pt 1537);

Governor of Ekiti State and Ors v Olubunmo [2017] 3 NWLR (pt 1551).

Culled: Supreme Court of Nigeria Website